The Chaos Theorem and Republican Division

Why the dogfighting will get worse

In 2025, Republican infighting has become increasingly public. Conservative influencers went on the offensive as Trump refused to release the Epstein files; Marjorie Taylor Greene, once a stalwart of Trumpism, has turned on her former Pope, who has referred to her as “very dumb”; Ben Shapiro has crossed swords with Tucker Carlsen over his coddling of Nick Fuentes; the Heritage Foundation has fallen apart over the same issue; Candace Owens has taken aim at Erika Kirk; everyone else has taken aim at Candace Owens; and nobody likes Mike Johnson.

Oh and I haven’t even mentioned the fun shenanigans involving Elon Musk in the first part of the year, but let’s not dwell on the past.

Chaos is clearly brewing inside the Republican party. But few know that this chaos has a name, and that name is Richard McKelvey.

A Primer on Social Choice Theory

Many of my readers may have heard of Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem. Colloquial accounts of the theorem state that “no ideal voting system exists”. A more academic definition would be that no voting system exists that guarantees (1) if everyone votes for you, you win (2) there’s no dictator (3) if A beats B and B beats C, A beats C (4) the choice between A and B depends on people’s relative preferences of those two, and not any other alternatives.

Since Arrow’s Theorem, economists and political scientists (henceforth “math-knowers”) have tried to work around it and develop conditions where a voting system can still work. Or at least sort of work. This is the field of social choice theory.

One equally well-known insight from this field is the median voter theorem. The statement is quite simple: if we can line up individuals in society on a one-dimensional left-right spectrum depending on their policy views, then there is one policy which would beat all other policies in a head-to-head matchup. That is, the preference of the median voter.

For a simple example, suppose five individuals have their own ideal tax rate, with the ideal tax rates being: 0%, 10%, 15%, 30%, 50%. If we had them vote between two alternatives at a time, 15% would never lose. If paired against 0% or 10%, then those whose ideal points are 30% and 50% would vote for it. And, vice versa if it is paired against 30% or 50%.

But, as noted above, the median voter theorem depends on a very special assumption: that we can line up individuals on a one-dimensional left-right spectrum. If this is impossible, then we’ll quickly find ourselves in trouble and back to Arrow land. To understand the implications of this, let’s return to the real world.

Diversity, yay! (Republican’s Version)

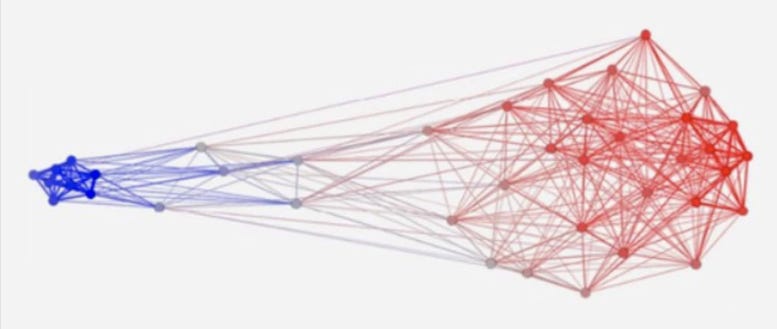

Chances are you’ve seen this image already. It maps political agreements in the United States. More specifically, it demonstrates that there is far more political agreement in the Democratic party than the Republican party.

Many have interpreted this as meaning that the right is more politically diverse. This is indeed true. The Republicans are an uneasy coalition of libertarians, Christian conservatives, populists, white nationalists, and the Tech Right. Meanwhile the Democrats pretty much all agree on the general direction in which they want to take the country. Their disagreements are more on the degree of left-wingness that they prefer.

Or to put it in social choice terms, the Democrats can be placed on a left-right spectrum pretty easily, while the Republicans cannot. In the Democratic party, individuals who are more left-wing on social issues such as abortion and LGBT rights are also more likely to be left-wing on economic policy. Think AOC. And those who are moderates on some issues are also more likely to be moderates everywhere. Think Joe Manchin (technically no longer a Democrat, but come on).

This is in large part why the Democrats, despite being self-hating and depressive, are able to not murder one another, while Republicans have resorted to name-calling. The Democrats, having preferences that can be mapped on a one-dimensional axis, are well-described by the median voter theorem. The Republicans, in contrast, are a better fit for McKelvey’s Chaos Theorem.

So…Who’s McKelvey?

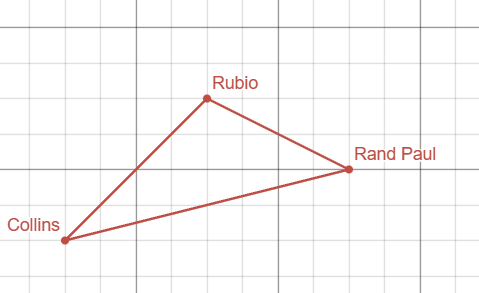

Imagine the standard two-dimensional political compass. Put social issues on the vertical axis and economic issues on the horizontal axis. Let’s take three prominent Republicans and try to place them: Rand Paul, Susan Collins, Marco Rubio.

Rand Paul, being a libertarian, is the most socially liberal and economically right-wing. Rubio, being a standard conservative is somewhat less right-wing economically and more socially conservative. Meanwhile Collins is moderate on both issues. What do our political positions look like?

Something like this. Now ask yourself: if the above three were to vote on a combination of social and economic policy by pointing to a spot on this 2D plane, what point would be chosen?

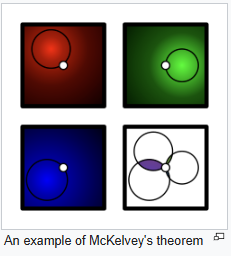

One intuitive answer is that they might pick the center of the triangle formed by their three points (which I’ve graphed above to save us time). This intuitive answer is quite elegant and completely wrong. Suppose Rubio, being the nicest of the bunch, offers up the center of the triangle as a compromise option. Rand Paul could instead offer the midpoint between his and Collins’ ideal position. Since both he and Collins would prefer that, it would beat the center of the triangle. Rubio could then counter by offering Collins a point in-between their ideal positions, but somewhat favoring Collins so that she switches and beats Rand Paul’s offer. Rand Paul might then decide to make a #guysteam with Rubio and just offer Rubio their midpoint. Rinse repeat. This game has no equilibrium, there is no “core”. There is no policy that won’t lose to some other policy. Instead, it’s just chaos. That is what McKelvey’s theorem shows us. If you’re unable to map policy onto a singular dimension, then you’re in deep trouble.

(And, in fact, McKelvey showed that a point *outside* the triangle could beat points inside the triangle, which is where the real headache begins).

What Does the Future Hold?

Republican woes are only just beginning. Going back to Arrow’s Theorem, Republicans’ one defense from complete chaos is that they have a dictator. Trump acts as a mean bully that punishes all who get out of line. But the dictator’s days are numbered. He will either continue to lose popularity with mounting scandals and economic disappointment, or eventually just lose control after the 2028 election.

Their current hope is that JD Vance and Marco Rubio will run on a “unity ticket” in 2028. But even then, how welcome will this combination be? Nick Fuentes, a growing figure on the right, constantly attacks Vance as something of a race-traitor. Shapiro, the antipode of Fuentes in the current Republican party, is instead at unease due to Vance’s quasi-isolationist foreign policy views.

Will a hypothetical 2028 Vance commit to defending Israel? How will Carlsen, Owens, Fuentes, and the “new” Republican media giants react to this? If not, should he hope for the endorsement of the WSJ, Fox News, and traditional Conservative media? Either way, it’s difficult to imagine the future of this party without a dramatic showdown where the gloves fully come off.

So, again: chaos.

The line of argument in this text is very interesting, but I think it could be made more explicit. I am certainly capable of drawing some inferences about what McKelvey’s theorem is, and those inferences might well be correct, but the text would have been better if it contained a sentence like: “McKelvey’s theorem is X, and you can see its operation at work right here.” At this point, I don’t really know if McKelvey’s theorem is only applicable to 2-dimensional spaces or if it is of broader scope, or if the notion of McKelvey’s theorem is not entirely formalized , etc.

Source of the first image? I’d always suspected it was the case. Very interesting to see it represented in data.