Protect Powell

A historical Fed Chairman is under attack

Today the Justice Department announced an investigation into Jerome Powell regarding Federal Reserve Headquarter renovations. Naturally, the proceedings have little to do with said renovations, it is another in a long line of attacks on Federal Reserve independence. To be brief, the President wants the Federal Reserve to lower interest rates. He thinks that this will make his supporters happy and possibly drive economic activity. Jerome Powell has resisted, given fears of high inflation.

Here I will attempt to convince you that Powell has been a good Chairman of the Fed. And, if anything, has erred on the side of leaving interest rates too low, not too high. I will also give a forewarning of what can go wrong in case the Fed loses its independence.

Early Issues

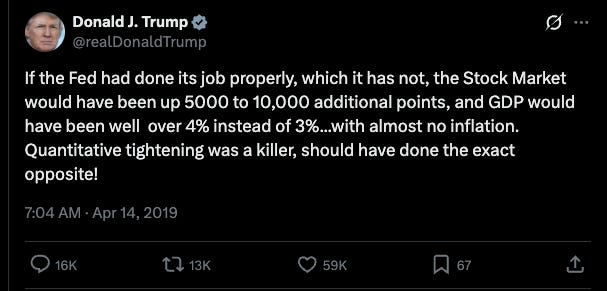

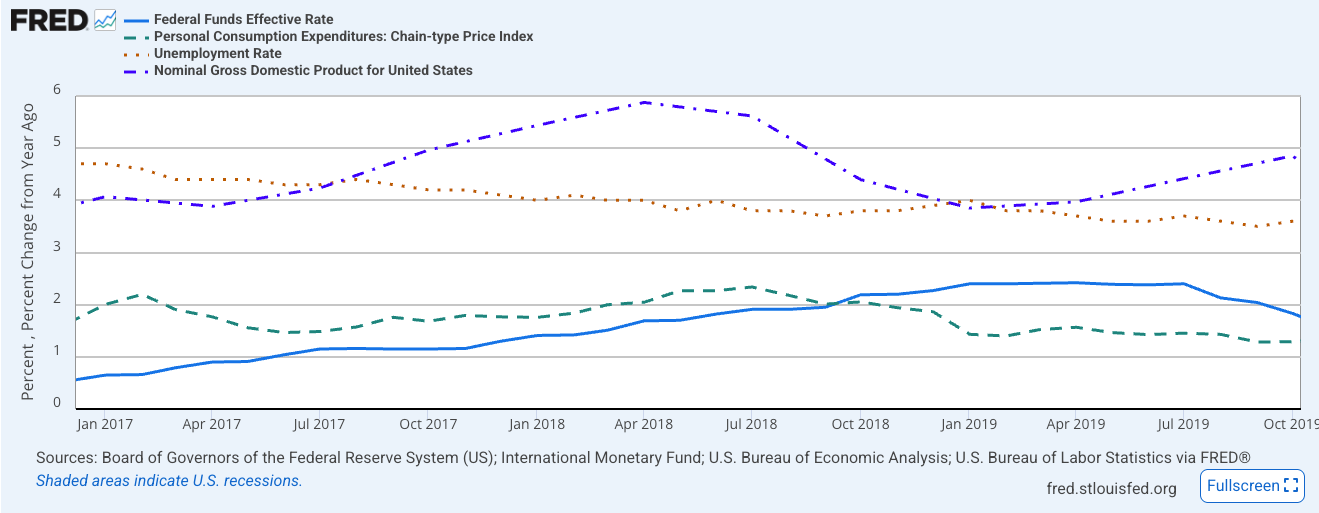

Powell took the office of Fed Chair in 2018. The first two years of his chairmanship were fairly standard. Powell continued Janet Yellen’s policy of raising the Federal Funds Rate from the zero level it had hit during the Great Recession. In 2019, this drew the ire of Trump, who claimed that Powell was keeping the stock market down and that easier policy from Powell would have resulted in larger GDP gains, with little to no inflation.

There are some criticisms to be made of Powell’s decisions at this point. In 2019 the inflation rate was persistently under target, but higher inflation was clearly not Trump’s goal. Lower interest rates would have likely failed at stimulating the economy given that unemployment was near 3.5% and nominal GDP was growing at a 4% yearly rate, which is the rate of demand increase consistent with 2% inflation in the long run, given the economy’s 2% productivity growth.

Courage to Act

Powell’s true test came a year later amidst the Covid-19 Pandemic. The US economy quickly crashed with unemployment peaking at almost 15%. Immediately this spawned discussions of how the recovery would look. Economists split into camps predicting that the aftermath of the virus would result in either a “V-shaped” recession, or an “L-shaped” recession. The former refers to a swift recovery where the economy quickly drops and quickly rebounds, such as during the Reagan years. The latter refers to a drawn-out and slow growth path such as in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis.

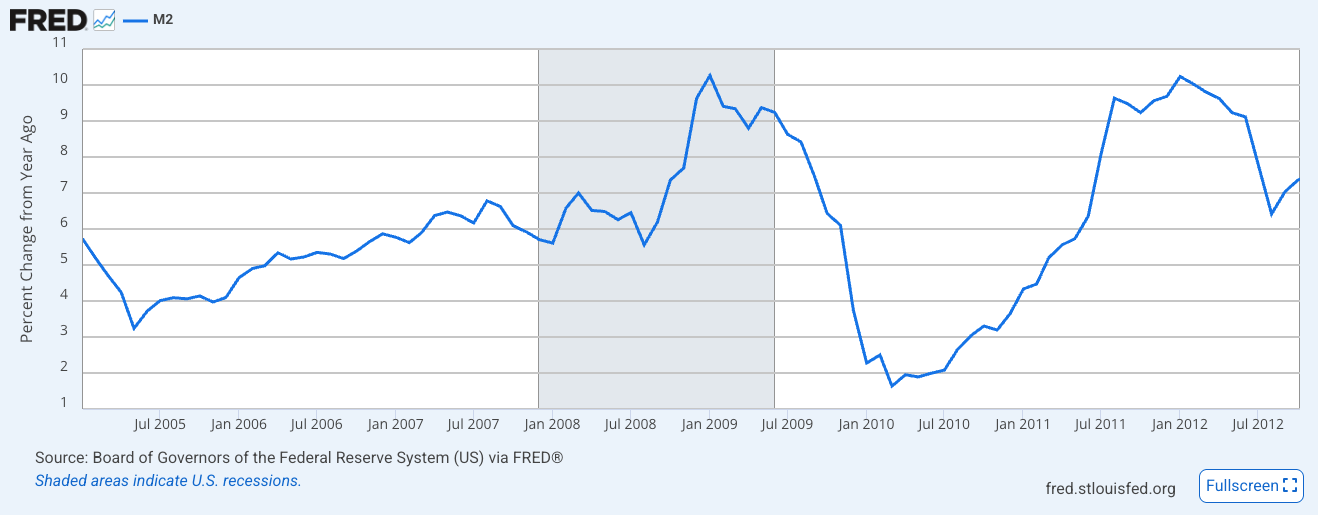

For those who understand monetary policy, the correct answer was obvious: it depends on the Fed. There is no fundamental reason why the Great Depression or the Great Recession of 2008 had to be “Great”. Both were driven by major central bank errors. Since this is not a post regarding either crisis, I will be brief: the prevailing reason for the Great Depression relates to the Federal Reserve allowing the broad money supply (M2) to drop significantly. This led to a collapse in spending, which automatically implies a collapse in nominal incomes (because one man’s spending is another man’s income). The collapse in nominal incomes induces firms to either (1) lower pay or (2) fire workers. We know that firms are extremely reluctant to lower wages, as such they fire workers. This results in greater reductions in spending, and the cycle continues. It did not matter that interest rates also fell, they did not indicate loose monetary policy, but rather deteriorating economic conditions.

This view is not controversial. It was developed by Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz in their seminal work A Monetary History of the United States. Later authors such as Romer & Romer agreed that the end of the Great Depression was also due to looser monetary policy. In fact, the most popular person to agree with this point is none other than Ben Bernanke, 2022 economics Nobel Laureate and Fed Chairman during the 2008 crisis. Bernanke, speaking at Friedman’s ninetieth birthday famously said: “I would like to say to Milton and Anna: Regarding the Great Depression. You’re right, we did it. We’re very sorry. But thanks to you, we won’t do it again.”

And then, they did it again.

Bernanke, refusing to make the same mistakes as the Federal Reserve of the 1920s and 30s, conducted significantly looser monetary policy during the Great Recession. He understood a simple truth: interest rates are not the same as monetary policy. Lowering interest rates may not be enough to stop a crisis if the rate necessary to stimulate spending is falling even faster (for a more detailed explanation of this, see my post here). As a result, Bernanke, by adding on top his now trademark policy of quantitative easing, was able to stabilize the M2 money supply (Friedman’s favourite metric), but failed in stabilizing its growth rate.

Through Bernanke’s efforts, which saw great public and institutional resistance at the time, the United States avoided a second Great Depression, but was unable to recover from the crisis quickly. Nominal GDP growth lagged behind, and the Fed ultimately remained behind the curve. Bernanke was likely the ideal person for the job, having spent his entire life studying a similar crisis, but even he was unable to force through the changes necessary to recover from a major economic crisis.

Enter: Powell 2020.

As Covid shocked the world, Powell faced the same issues as previous Fed Chairs in similar circumstances. How can one stabilize the economy if interest rates are already at zero and have no room to go lower? Bernanke’s answer had been quantitative easing, but it had proved insufficient. As many would argue, Bernanke’s quantitative easing simply included swapping bonds that already paid 0% interest for cash, which also paid 0% interest. As a result, its stimulative effects were benign. Furthermore, the Federal Reserve maintained a 2% target for inflation, if quantitative easing were to have a truly large effect on demand, the financial sector expected that the Fed would turn and quickly tighten policy to get inflation under control. This implied that short-term decisions may not be enough.

To combat this conundrum, Powell made two important changes. The first was a switch to “flexible average inflation targeting”. This meant that the Federal Reserve would make up for missing its inflation target in previous years. If inflation undershot by 1%, the Fed would aim for an extra 1% inflation in the next few years. This seemingly small tweak had massive consequences: at 0% nominal interest rates, the public could now expect higher inflation. Meaning that real interest rates would go down. And if the Fed kept undershooting its target, the commitment to higher inflation became even greater. This solved the issue that worried the financial sector: higher inflation would no longer be met with immediate tightening.

The second issue was that the Fed needed to signal its willingness to do whatever it takes to stimulate the economy. As Bernanke said in a speech from 2000, if the central bank indicates a willingness to buy up all the assets in the world, then spending must increase, or we’ll end up in paradoxical circumstances where the central bank owns the planet. Powell, not afraid of bold moves, indicated his willingness to do whatever it takes by starting purchases of corporate bonds, something that was hitherto unheard of. This move remains controversial and may have even been unnecessary, but made clear that the Fed would stop at nothing to return the economy to good health.

The result was, by all means, a historic success. By end of 2021, unemployment was already under 4%. It had taken the United States ten years after the Great Recession to achieve that point.

Loosey Goosey

As the economy continued to recover, many analysts (most famously Larry Summers and Olivier Blanchard) noted that inflation had gone above target and predicted that it would not fall. The economics profession split into two broad camps: team persistent and team transitory. The former believed that inflation was here to stay and that (1) the government should refrain from further fiscal stimulus (2) the Fed needed to raise interest rates now. The latter group claimed that inflation had been caused by temporary factors that would sort themselves out.

This is where Powell made his biggest mistake. The Fed implicitly adopted the “team transitory” position for much of 2021, keeping interest rates at 0% and even continuing to engage in quantitative easing! This transpired even as nominal GDP was growing at double-digit rates, unemployment was below 4%, and the PCE price index was growing at 6% yearly rates.

But even more importantly, the Powell Fed messed up its framework. The “flexible average inflation targeting” framework developed earlier was extremely well-equipped to deal with these circumstances. Even if the Fed were wrong about transitory inflation, its commitment to average inflation targeting would have meant that overshoots of its target would be followed by sub-2% inflation in following years. This would result in a fall in inflation expectations and make the disinflation that much easier. Unfortunately, the Fed indicated that overshoots would not be followed by undershoots, effectively making “flexible average inflation targeting” into some strange asymmetric price level target. This killed the chance for a swift disinflation.

Once in a Lifetime

Despite Powell’s major mistakes in the early inflationary period, the Fed soon reversed course and began to rapidly raise interest rates. Sometimes raising rates by 0.75%, something that US policymakers had shied away from. Though Powell was playing a suboptimal strategy having abandoned FAIT, he performed a miracle of monetary policy: despite broad forecasts of an impending recession and unemployment, Powell raised rates to a staggering range of 5.25-5.5% while unemployment did not go above 4.2% (at least until Liberty Day).

This is no mean feat. Paul Volcker’s attempts at disinflation resulted in a peak unemployment rate of 10.8%. Even when he and Reagan achieved “Morning in America”, inflation was above 4%, with unemployment shy of 8%. Numbers that would shock the American consumer today.

Powell’s “soft landing” was a once-in-a-generational achievement. Its primary cause was the Fed’s credibility. Disinflations cause unemployment largely because nominal GDP growth falls far below what people expected. This means that firms bring in less income than they had planned, leading to firings. But if inflationary periods do not result in higher expected inflation, then lowering inflation can be near-costless because firms never begin to expect unrealistic nominal income growth in the first place. I made this case in 2023, arguing that a soft landing was close.

But today, the Trump administration threatens a Federal Reserve Chairman who has been historically successful. Powell, for all his mistakes in 2021, showed us how a simple framework change can lead to a rapid recovery from a major global disruption. His careful decision making largely made up for his mistakes during the inflationary surge and made good use of the Fed’s reputation. It is precisely that reputation that the Trump administration may unintentionally destroy.

If the Chairman of the Fed becomes subservient to the President’s wishes, then the consequences could be disastrous. First, the central bank will have an “inflationary bias”, an urge to pursue loose monetary policy for short-term political gain. The United States went through this when the Nixon administration applied pressure to then-Chairman Arthur Burns, resulting in the debacle of the 70s. Second, the Fed would lose its credibility as an inflation-fighter. This would make future disinflations extremely painful. If the public stops believing in the Fed’s 2% inflation target, then a soft landing like in 2023-2024 will become impossible - future landings will involve high unemployment and a recessionary shock.

Finally, one need not look far and back. Just a few years ago, President Erdogan of Turkey decided that central bankers were unintelligent and should simply lower interest rates since that had to be good. The result was not great.